by Miykael Qorbanyahu

___________________________________________________________

If a man sees that sufferings have come upon him, let him scrutinize his deeds, as it is said: ‘Let us search and try our ways, and return unto [HaShem – the Name]’ [Lamentations 3: 40]. If he did scrutinize his deeds without finding [any sin for which he would deserve to suffer] let him attribute it [the suffering] to the sin of neglect of the Torah [i.e. there may be no sin of commission for which he deserves to be punished, but there may be, nevertheless, this serious sin of omission], as it is said: ‘Happy is the man whom You chasten, and teach out of YourTorah’ [Psalms 94: 12; i.e. (Elohim) chastises a man so that he should return to the study of the Torah]. If he did attribute his sufferings to his neglect of the Torah without finding [that he has been indolent in study of the Torah], it then becomes known that they are sufferings of love, as it is said: ‘For whom [HaShem] loves He corrects [Proverbs 3: 12].

Biblical and Rabbinic Responses to Suffering

For I reckon that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the esteem that is to be revealed in us.

Romans 8.18

___________________________________________________________

Throughout my college football career, pain wasn’t just something that popped up in my life, it was more like a companion. My journey as a student-athlete at the University of Maine from 93-98 was marked by a series of brutal, character-shaping injuries that tested more than just my body; they tested my spirit. My freshman year, I suffered a hairline fracture to my jaw from a full-contact tackling drill which was my introduction to a life of physical suffering on a new level. After starting my very first college football game, I was forced to redshirt after getting my jaw wired shut after my Bryan Hawkes cracked me with his helmet during form tackling drills. Eventually, I returned after rehab ready for the next season, hungry to prove myself. Sophomore year, I faced chronic shoulder stingers caused by a narrow spinal column that would flare up after the relentless impacts of the game. Still, I pressed on. By my redshirt sophomore year, the consequences of neglecting an old high school injury caught up with me, as a left shoulder subluxation led to a major surgery. Even then, I rehabbed fiercely, came back early, and balled out, playing 6 of 11 games and putting together one of my best seasons. But it was my senior year that broke me. While playing basketball before spring ball with some of my teammates, I tore my ACL. I tried to power through without surgery, but almost every time I tried to moved laterally, my knee buckled. Eventually, I had no choice, and I went under the knife, rehabbed, and tried to come back again, but this time, my knee wouldn’t hold. Fall of 1996 was the end of football for me. Letting go wasn’t just painful, it was disorienting because I couldn’t be with my first love anymore. I had to rediscover who I was without the game. Enter my spiritual quest.

Fast forward years later, and a different kind of pain surfaced, emotional pain. The kind you don’t limp away from, but carry in your chest. The kind that twists you up late at night when you thought you’d already healed. This particular wave of emotional pain began during my last year of college, triggered by an experience with an ex-girlfriend. She would turn to me for emotional comfort while finding physical pleasure with others. As a hopeless afromantic, I kept showing up for her, hoping to rekindle what we once had. Needless to say, that season taught me a lesson about emotional boundaries and self-worth.

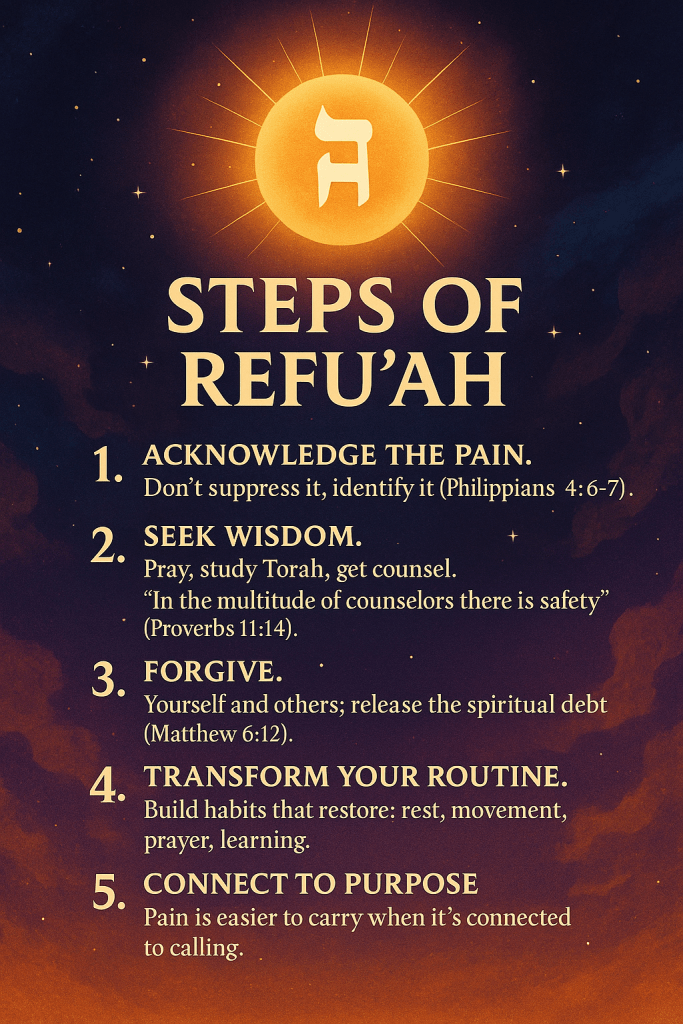

Looking back over my relationship history, a pattern reveals itself, one I can no longer ignore. For much of my adult life, I’ve entered relationships not out of spiritual alignment or shared purpose, but from a place of ego. I was often drawn to appearances, physical chemistry, and the validation of being desired, rather than taking the time to evaluate compatibility of values, vision, or calling. My earlier marriages were rooted in convenience and a desire to change my lifestyle, attempts to outrun my brokenness instead of confronting and healing it. I entered those unions prematurely, hoping that partnership would serve as a substitute for inner restoration.

It wasn’t until my most recent marriage that I came into the relationship whole. I had done the work. I had grown into someone capable of loving from a healed place. And still, I found myself attached more to an image, an idealized vision, than to an actual shared foundation of values and mutual understanding. I truly believed we had a common mission and alignment of purpose, but in hindsight, it was another egoic attachment dressed up as divine assignment. That doesn’t mean the love I gave or received was inauthentic, it wasn’t. But the pain I felt was still deep. Disappointment, in myself, in her, in our dynamic, left a mark. And from that pain, new insight emerged: that even love, when misaligned, can become a source of suffering, and that pain, in its many forms, still has something to teach.

What’s more, this most recent experience has taught me a great deal about giving, vulnerability, transparency, confrontation and what it truly means to show up for another person. But it also came with pain, a deeply felt pain, especially when who we are, or who we’ve become, doesn’t meet the expectations of those we love. Yet, it’s in that pain that the mirror appears. It shows us what’s unresolved, what still hurts, and what still needs healing. It is during these times that pain becomes the prophet, whispering truths we might otherwise ignore. And if we’re willing to listen, it can guide us not just into healing, but into becoming, into transfiguration.

The beautiful thing about this experience is that now that I’m back with myself, I enjoying the process of working on myself. Just before the marriage ended, I had decided to go on a 90 day retention journey, which is a big challenge for me, and since then, I’ve written 23 pieces, with this one here. Pouring myself into making sense of myself, I’m learning even more so now how to be whole, by myself. I’ve started developing the muscles of love from within. I’m focused on becoming emotionally honest, spiritually rooted, and physically disciplined. And I can’t front at all, this journey is far from easy, but this work is giving birth to wisdom, and eventually, I know that my ability to love will not be out of deficit, but out of overflow; in the right time and in the right season.

In all this, I’ve come to know for certain that pain has a purpose. Life isn’t about escaping pain. Torah doesn’t teach us to numb it or avoid it, like time and seasons, it teaches us to discern it. Even Mashiach Yeshua, the Suffering Servant (Yeshayahu/Isaiah 53), bore pain and affliction not because He deserved it, but because the redemption of others was tied to His endurance. “He was wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities…” Through His personal pain, came universal healing. That’s not just theology. That’s a pattern. A sacred path. Not that my pain is for the universal healing of humanity, but my experience will be able to lend to other who have gone through similar experiences, and in that, the universal principles of healing will find their place in the life of another in need of their modalities.

This principle, of pain producing purpose, is not exclusive to one story or one person. It’s a thread woven through the lives of those who’ve dared to surrender their suffering to something greater. When we choose to perceive our pain not as punishment, but as a preparation for purpose, we align ourselves with the Universal blueprint. That’s when transformation truly begins, when pain is no longer just something we endure, but something that instructs and awakens us.

Take Yosef ben Israel aka Joseph son of Israel. Betrayed by his own blood, thrown into a pit, falsely accused, forgotten in prison. But he didn’t stay bitter. He allowed his pain to birth a deeper purpose, preserving a nation. Then there’s Shimshon (Samson), who had raw power but lacked restraint. His betrayals and pain led him to vengeance and destruction, but even in the end, YaH used it to bring justice. These stories are Torah-based blueprints for how pain can serve purpose when surrendered to Elohim.

As transparent and as real as I know how to be with you, beloved reader, I’ll admit with no shame that I haven’t always done healing right. There were times I was the walking embodiment of the phrase “hurt people hurt people.” I manipulated and exploited people, lashed out, pushed people away, stayed distant out of fear of being seen; you name it, I’ve done it. But growth came when I stopped avoiding the pain and started confronting it, and that’s when my healing began.

In Hebrew, the word for healing is Refuah (רְפוּאָה). The Dictionary of Torah Names and Words provides us with a profound insight into the Hebraic idiom of what healing is all about.

to remedy, heal; to mend by invigorating principle, making great; lit., the nobility of mind expressing principles of Light to attain wellness and fullness; healing often occurs when the principle of Light becomes paramount due to decreased emphasis on the physical, in which case factors of illness weaken and perish…

This definition emphasizes healing not just as a physical restoration but as a spiritual and intellectual transformation. To remedy or heal in this context means to mend by connecting with an invigorating principle, a noble state of mind rooted in Light (wisdom, truth, and divine awareness). The phrase “nobility of mind” suggests that true healing comes when we rise above carnal or ego-based reactions and allow the principles of Light to guide our perception and response to suffering.

This relates directly to the transformative power of pain and the Transfiguration Movement, which calls us to elevate our consciousness through our trials rather than be consumed by them. Pain strips away distractions, forcing us to look within and seek a higher truth. When the physical becomes less of a focus, either through affliction or reflection, spiritual clarity becomes possible.

In this way, pain becomes a sacred tool for tikkun (repair). It humbles the ego, exposes inner fractures, and invites the Light to mend what’s been broken. The Transfiguration Movement understands pain as a gateway: it is not merely to be endured but engaged with, so that we emerge reformed, refined, and aligned with our purpose. The deeper the pain, the greater the potential for transfiguration, if we choose Light over bitterness and purpose over pride.

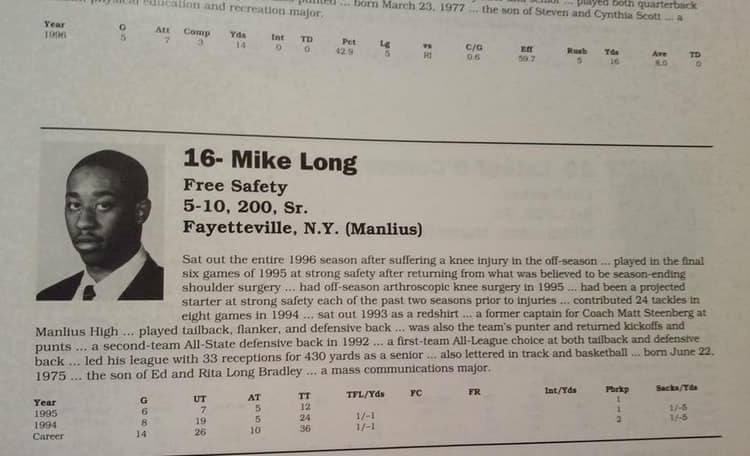

More insight into the word refuah is extracted when we consider what each letter speaks:

- Resh (ר) – A head, the beginning, a shift in consciousness.

- Fe (פ) – A mouth, expressing truth, releasing confession and praise.

- Vav (ו) – A connector, symbol of binding heaven and earth, bringing alignment.

- Aleph (א) – The first, representing YaH, the breath of life.

- Hei (ה) – the window, breath, revelation, divine presence being expressed outward, a symbol of grace and spiritual insight.

From these letters, we get the following message:

“When the head is renewed (Resh), the mouth releases truth (Pe), and the connection between heaven and earth is made (Vav), guided by the breath of Elohim (Aleph), allowing for supernatural healing and revelation (Hei) to flow into being.”

In other words, healing isn’t just physical, it begins in the mind, confessed through the mouth, becomes aligned spiritually, rooted in the Holy Spirit, and is made visible through the revelation of Torah.

Adding to this powerful principle, according to the Zohar and the teachings of our sages, true refu’ah is a restoration of original design, a return to tikkun (repair, rectification). The word refu’ah thus encodes not only recovery but a returning to wholeness through spiritual alignment with Torah.

And so we should be able to clearly perceive from these insights that healing isn’t just a destination, it’s a process that starts with a renewed mindset, involves honest expression, aligns us with higher purpose, and breathes life back into us.

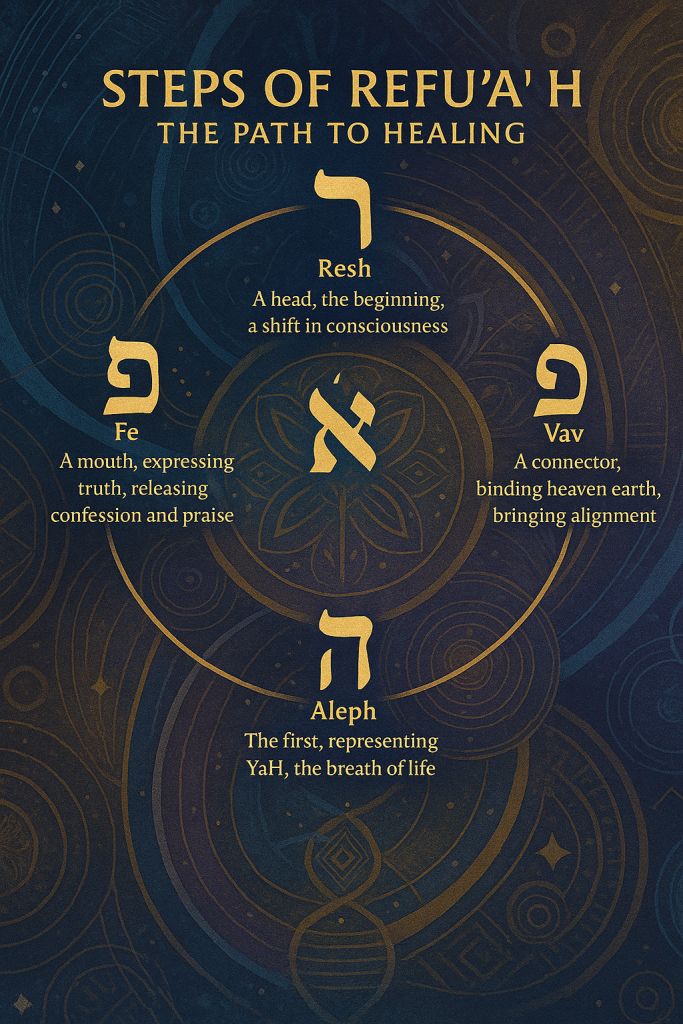

So how do we begin to heal?

- Acknowledge the pain. Don’t suppress it, identify it (Philippians 4.5-7).

- Seek wisdom. Pray, study Torah, get counsel. “In the multitude of counselors there is safety” (Mishlei/Proverbs 11:14).

- Forgive. Yourself and others; release the spiritual debt (Matthew 6.12).

- Transform your routine. Build habits that restore: rest, movement, prayer, learning.

- Connect to purpose. Pain is easier to carry when it’s connected to calling.

Oral tradition teaches us that in the days of Mashiach, the very wounds will become vessels of light, portals through which the Shekinah Presence is revealed. This profound teaching aligns with the work of platforms like Tikkun HaBerit, which provides spiritual tools designed for the repair of covenant (tikkun), soul restoration, and deep inner healing. Among these tools are teshuvah (repentance), tefillah (prayer), and ta’anit (fasting); ancient disciplines that allow us to confront our pain, purify our intentions, and reconnect with the Source.

Teshuvah, or returning to our highest self through truth and accountability, softens the hardened places within us that pain often calcifies. Tefillah, the sincere and structured articulation of our needs and hopes, brings us into direct dialogue with YaH, creating space for supernatural comfort and guidance. And ta’anit, purposeful fasting, quiets the noise of the flesh so the soul’s voice can rise with clarity. These are not mere rituals, they are sacred technologies of transformation. Each of these practices helps transmute pain from a place of suffering into a wellspring of wisdom and compassion, reminding us that the pathway to healing is already encoded in the covenant we carry.

That’s why pain is part of the Transfiguration Movement. It’s a necessary stage in the process of our becoming, a sacred fire that burns away illusions and lies. Because let’s be honest, we all know that growth hurts. Muscles tear before they strengthen, bones reset after they break, hearts ache before they open, but it’s in that ache that we are transformed.

So my brothers, my sisters, let your pain speak, but don’t let it dictate!

Listen to it.

Learn from it.

Convert it into your purpose.

Let your wounds become windows.

Let your scars tell stories.

Let your pain become prophecy.

Because even the Mashiach had to suffer before He was esteemed, and if we are to follow Him, then our pain isn’t in vain, it’s the womb of our becoming.

Let your pain begin your inner transfiguration.

Selah…

Discover more from SHFTNG PRDGMZ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.