____________________________________________________________

The Torah scholar should not walk with erect stature and head held high (lit., ‘throat thrust out’) as it states ‘[…for the daughters of Zion are haughty,] and they walk with outstretched throats and gazing (or winking) eyes’ (Isaiah 3:16). He should not walk [in small, delicate steps, placing his] heel beside [his other foot’s] big toe, casually, as do women and the arrogant, as it states, ‘…walking and floating do they go, and with their legs they entice’ (ibid., end of verse). [The Torah scholar] should not run in public and act crazily. He should also not bend his stature [in exaggerated fashion] as a hunchback. Rather, he should look downwards [slightly] as one standing in prayer. And he should walk even-paced as one busy with his matters. Even from a person’s gait it is discernible if he is a scholar possessing wisdom or a madman and fool. So too did Solomon say in his wisdom, ‘Even along the way, as the fool walks, his heart is lacking and he proclaims to all he is a fool’ (Koheles (Ecclesiastes) 10:3). He informs all regarding himself that he is a fool.

The Rambam – Rabbi Maimonides

The Torah of יהוה is perfect, bringing back the being; the witness of יהוה is trustworthy, making wise the simple; the orders of יהוה are straight, rejoicing the heart; the command of יהוה is clear, enlightening the eyes; the fear of יהוה is clean, standing forever; the right-rulings of יהוה are true, they are righteous altogether, more desirable than gold, than much fine gold; and sweeter than honey and the honeycomb. Also, Your servant is warned by them, In guarding them there is great reward.

Psalm 19.7-11

____________________________________________________________

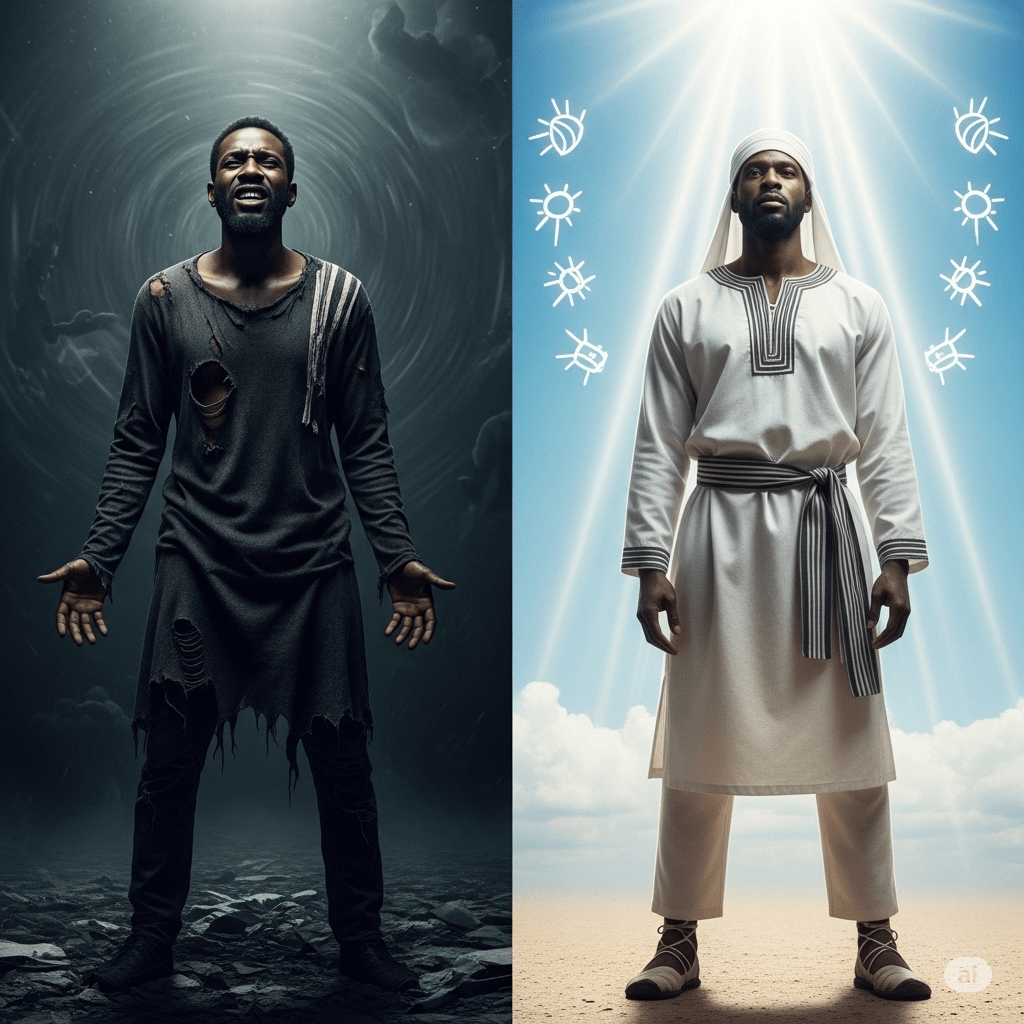

By now you know my story, but for the sake of this entry, let me remind you that there was a time not too long ago when my life was completely out of alignment with the will of YHWH. I’m talkin’ ‘bout no discipline, no boundaries, and no regard for the Torah’s instruction. I was deep in the moat and trenches: I’m talking about a fornicator, a drunkard, a liar. I abused my body, as well as others, and numbed myself in darkness because, honestly, it was easier to hide there. I found that the dark is warm when you’re cold inside. And in that state, sin ain’t just something you fall into, it becomes a rhythm. I’ll be the first to say that I’m nowhere near proud of when I was living in sin. And I didn’t know it then, but now I know that I was caught up in sin’s spin cycle.

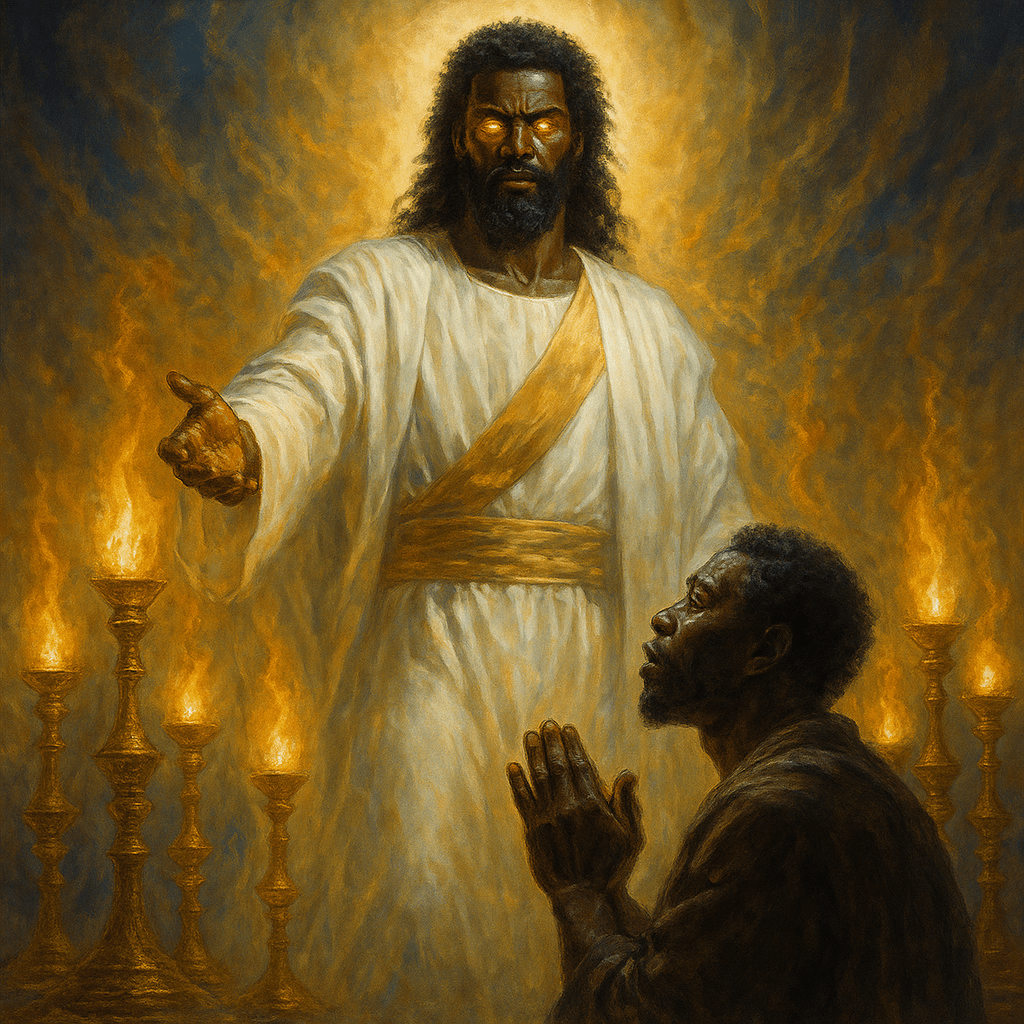

But when I found myself accepting the lies that I was telling myself, I knew it was time for a change. So I took upon myself to introduce myself to principles, not feelings; principles, not religion, I’m talking about principles, higher laws, unchanging dynamics, the fundamental essence of existence. It was then that I started questioning why I kept hitting the same wall, facing the same pain, feeling the same void. And somewhere in that soul-searching, the Most High began whispering the Truth to me. It wasn’t loud, but it was steady; it wasn’t blatant, but consistently subtle. And when I had my burning bush moment, that was when I had no choice but buckle down and decide to be intentional with my life. That’s when I started to feel that conviction, and it was because of that conviction that the Torah found me. Or maybe, that’s when I finally stopped running and let it catch up. Rav Shaul writes of this to the assembly at Corinth, explaining the role that conviction plays when it leads us back to the path upon which we are to walk. In 2 Corinthians 7.10-11 he wrote the following,

For sadness according to Elohim works repentance to deliverance, not to be regretted, but the sadness of the world works death. For see how you have been saddened according to Elohim – how much it worked out in you eagerness; indeed, clearing of yourselves; indeed, displeasure; indeed, fear; indeed, longing; indeed, ardour; indeed, righting of wrong! In every way you proved yourselves to be clear in the matter.

And this is the beauty of the matter, that the Torah didn’t judge me; rather, it re-aligned me. My life started to shift, and I didn’t just believe different, I began walking different.

What does that mean, practically? It means everything changed, from the inside out. The Torah didn’t just put a new book in my hand; it put a new lens over my eyes, a new rhythm in my step, and a new appetite in my soul. One of the first things to shift was my diet. I stopped treating food like it had no spiritual impact. I began observing the dietary instructions laid out in Leviticus 11, not just because it was “law,” but because it was life. I first stopped eating pork and catfish, not out of fear, but out of fidelity. In 2001, I became a vegetarian because I began to see my body as a mikdash me’at, a small sanctuary, as what enters it matters.

Then my observances shifted. I started keeping Shabbat, not as a burden, but as a breath. That one day out of seven became my lifeline, a day to unplug from the matrix and reconnect with the Most High and myself. The Mo’edim, or Appointed Times, like Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot, began to replace the hollow days with holy days. These weren’t just traditions; they were holy encounters and appointments with YaH interwoven into the rhythm of life.

Even my language changed. Words I used to throw around casually, curses, slang rooted in violence or vulgarity, began to feel out of place in my mouth. I began using Hebrew phrases like shalom aleichem, todah rabah, and Baruch Hashem, not to sound deep, but because my tongue had to match my transformation. Because life and death are in the power of the tongue (Proverbs 18:21), I had to start speaking life. That transformation extended beyond how I greeted people or expressed thanks, it reached into my calendar too. I stopped using the conventional names for the days of the week and months of the year, because many of them are tied to pagan deities and idolatrous traditions. Sunday (the day of the sun), Thursday (Thor’s day), January (named after Janus), March (after Mars), these aren’t just names; they carry histories and meanings that don’t reflect the Kingdom. Additionally, we are commanded at Exodus 23.13 to not utter the names of other deities. So, instead I began calling the days by their Hebrew names: Yom Rishon (First Day), Yom Sheni (Second Day), and so on, all the way to Shabbat. I also began marking the months by the scriptural calendar. This wasn’t legalism, it was faithful alignment. I decided, if I’m going to live holy, then even the way I track time must reflect the Creator’s rhythm, not the world’s repetition.

My thoughts also evolved. I used to measure success by money, fame, and physical pleasure. But now, success looks like wisdom, self-control, justice, and love rooted in Truth. The Torah became my mirror and my map. As Psalm 119:105 says, “Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path.” My inner world, once dark and chaotic, began to align with heavenly order.

Naturally, my associations changed too. I couldn’t roll with the same crowd when my values shifted. That doesn’t mean I became better than anyone else, but I became different. I needed people who were pursuing purpose, not popularity; righteousness, not recklessness. Iron sharpens iron (Proverbs 27:17), and dull blades couldn’t sharpen the new me.

Even the places I used to hang out lost their appeal. The clubs, the bars, the strip clubs, the spots that inflamed the flesh, I just didn’t fit anymore. It wasn’t condemnation; it was conviction. I wasn’t trying to escape fun; I was attracted to fulfillment. I wanted places where the Spirit was welcome, where the Word could dwell, and where my presence added to the atmosphere of light.

And so when I say the Torah didn’t judge me, it re-aligned me, I simply mean that the Torah didn’t come to crush me; it came to cleanse me. It didn’t condemn me where I was, it called me into who I was destined to be. That’s the power of transfiguration. Not just learning what’s right, but living it. Not just a changed belief system, but a changed lifestyle. I didn’t just know better, I now had to ensure that I walked better. And that’s the fruit of the Spirit of Truth working through the Torah of Life.

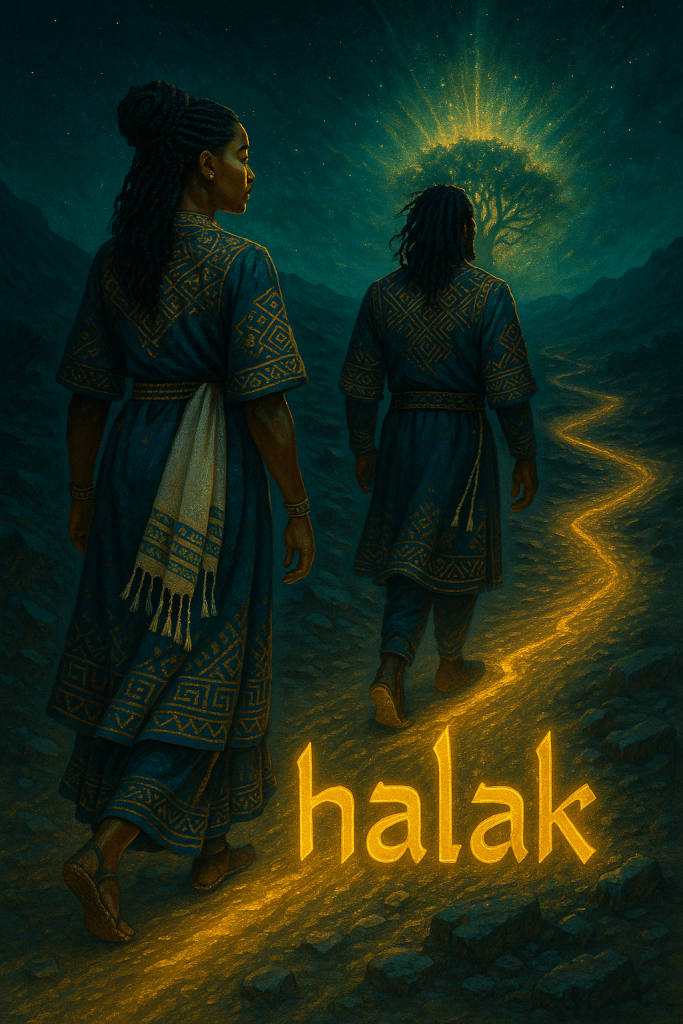

See, in Hebrew, the word for walk is halak (הָלַךְ). And it’s more than just putting one foot in front of the other, it’s a lifestyle, a path, a journey. It’s where we get the word halakhah (הֲלָכָה), which refers to how we walk out the commandments in daily life. Not just how we think about righteousness, but how we live it. Halak is what defines movement with purpose, it’s about walking in rhythm with the Ruach (Spirit) and in alignment with the instructions of the Most High.

The Hebrew word halak (הָלַךְ), meaning to walk or to go, is composed of three letters: hei (ה), lamed (ל), and kaf (ך). Each of these letters carries deep symbolic meaning that, when combined, offers insight into the spiritual nature of walking—both physically and in the context of living out Torah, or orthopraxy.

Hei (ה) represents divine breath, revelation, and presence. It is often associated with the Ruach (Spirit), indicating inspiration or something revealed from above. As the first letter of halak, it suggests that our walk begins with a divine spark—YHWH’s breath animating our steps and setting us on the path.

Lamed (ל) is the tallest letter in the Hebrew alphabet, often seen as reaching upward like a shepherd’s staff. It symbolizes teaching, learning, and leadership. Placed in the center of halak, it shows that our walk must be guided by instruction—specifically, the Torah, which trains and elevates the soul. It’s not enough to walk—we must walk with understanding and intention.

Kaf (ך) represents the palm of the hand, the ability to receive and to act. It symbolizes capacity and potential. As the final letter in halak, it reveals that our walk is meant to manifest action and responsibility. It’s where intention becomes impact—where revelation and instruction find expression in how we carry ourselves.

Altogether, halak is a spiritual journey: the breath of revelation (hei) enters the soul, instruction and elevation (lamed) guide the way, and our capacity to act (kaf) completes the process. This is the very essence of orthopraxy, not just believing rightly, but walking rightly. To halak in the Torah is to transfigure, step by step, into the likeness of the Mashiyach, reflecting the image of Elohim in motion.

The psalmist lays it out plain in Psalm 119:1–6, how a blessing rests on those who are perfect in the way, those who walk in the Torah of YHWH. This isn’t abstract poetry, it’s a roadmap. It tells us that righteousness is not passive; it’s a path. The walk, the halakha, is the proof of our pursuit. It’s one thing to know His commands, but it’s another thing, entirely, to guard them diligently; to walk them out with consistency and conviction. When our ways are established in His ways, shame is removed and clarity is restored.

This is the heartbeat of orthopraxy, living a life so in sync with the Word that your behavior testifies louder than your beliefs. It’s the transformation of lifestyle that begins when we shift from just thinking about righteousness to doing righteousness. Because transfiguration doesn’t happen in theory, it happens in your walk.

The Torah never commanded us to just “believe” in holiness, it commands us to walk in it. “And now, Yisrael, what does YHWH your Elohim ask of you, but to fear YHWH your Elohim, to walk in all His ways, to love Him, and to serve YHWH your Elohim with all your heart and with all your soul?” (Deuteronomy 10:12). You see that, right? It said walk in all His ways. That’s halak.

Halakhic living, a life lived in obedience, is rooted in covenant, shaped by instruction. Contrary to conventional thought, it’s not about religious performance, it’s about prophetic posture. This is where people confuse religion with Kingdom lifestyle. It’s your steps reflecting your soul. That’s why transfiguration isn’t just about looking spiritually glowing, it’s about being morally grounded. When your walk starts matching your words, and your lifestyle becomes a visible sermon, then you’re stepping into the mystery of the Mashiyach.

In the synoptic witnesses, Yeshua said in John 14.6, “I am the Way, and the Truth, and the Life. No one comes to the Father except through Me.” To follow Him is to walk as He walked, to live halakhically. To be transformed in mind, word, and movement.

So ask yourself: what’s your halak? What’s your walk saying about your worship? Orthopraxy isn’t being perfect, it’s about the pursuit of it. And in this Transfiguration Movement, we’re not just studying the way, we’re walking it out, step by righteous step on the path.

In Hebrew, the word for “way” or “path” is דֶּרֶךְ (derek). It’s more than a road, it’s a manner of life, a direction, a lifestyle. It’s not just where you’re going, it’s how you’re going. In the Torah, derek is what the righteous walk on and the wicked depart from. It is the behavioral blueprint of those who align with Elohim.

But just for a light hearted moment, here’s a hilarious story about derek I have to share. The first time my best friend Shebaniyah and I heard someone say “you gotta walk in the derek,” we looked at each other like, “Who’s Derek and why everybody following him?” We legit thought Derek was some righteous elder with sandals, a tallit and a staff, leading people down a path to holiness. Turns out, “derek” wasn’t an elder, it was the way. Still, to this day, we joke like, “Man, if I ever meet a real Derek, he better be walking tight with Torah!”

But breaking this word down, derek is spelled dalet (ד), resh (ר), kaf (ך).

- Dalet (ד) is the door, representing decision and access.

- Resh (ר) represents the head, representing consciousness, leadership and beginnings.

- Kaf (ך) is the palm, related to capacity in order to receive and act.

Together, derek reveals this: The way you walk is a decision (dalet) that begins in your mind (resh) and manifests through your actions (kaf). Transfiguration, then, is not just about glowing on a mountaintop, it’s about walking in the way that leads to transformation. It’s about stepping out of the shadows of who you were and becoming the vessel you were always meant to be.

But here’s where it gets deeper: on a personal level, what really changed me wasn’t just what I believed, it was how I started living.

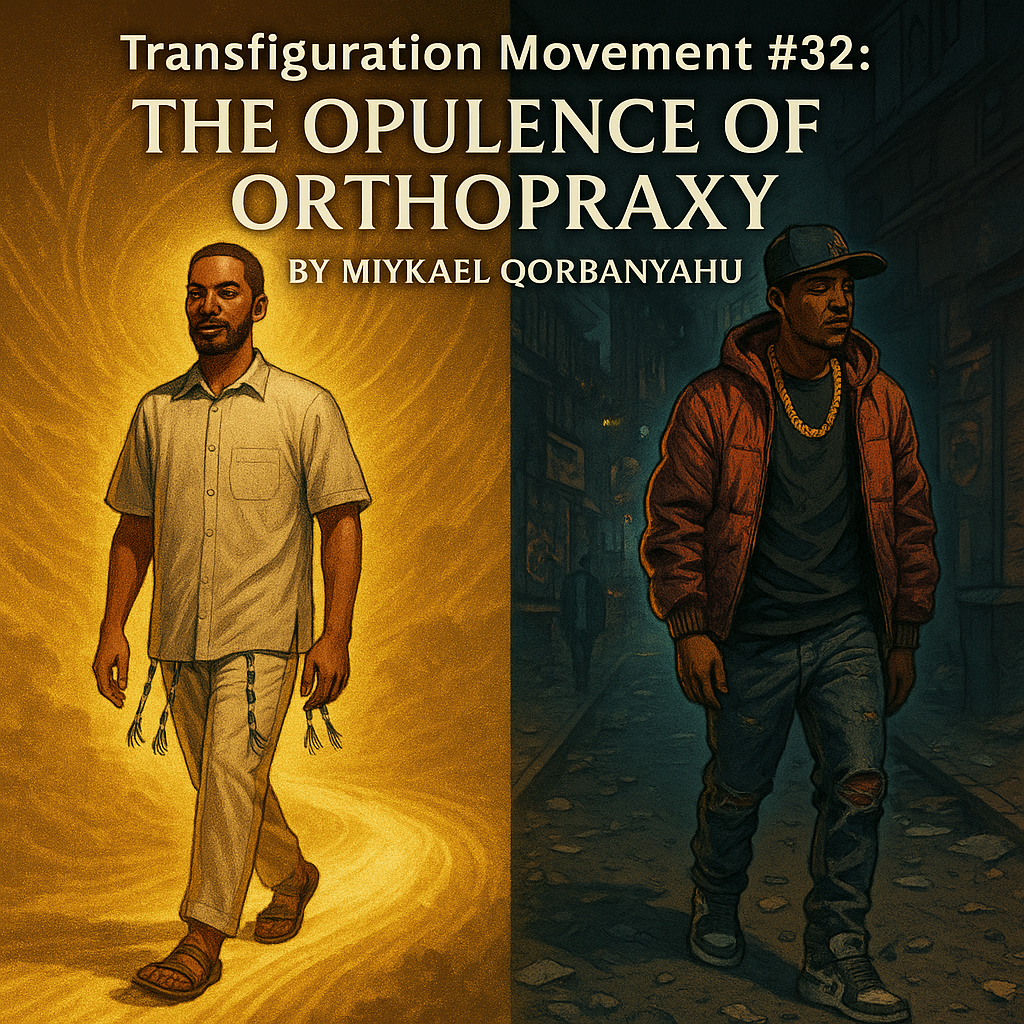

Enter the concept of orthopraxy: right practice. Not just right belief, which is connected to orthodoxy, but correct behavior. And in Torah culture, YHWH has always been about action. That’s why He gave us mitzvot (commandments). Not just thoughts, not just concepts, but instructions to do.

In fact, when we look into the book of Revelation and the messages given to the seven assemblies, there’s a consistent, piercing refrain that echoes like thunder from the mouth of the risen Messiah: “I know your works…” (Revelation 2:2, 2:9, 2:13, 2:19, 3:1, 3:8, 3:15). Not “I know your beliefs,” not “I know your good intentions,” but your works, your ma’asim in Hebrew, your ergon in Greek, your actions, your deeds, your behavior. This isn’t just poetic repetition; it’s prophetic emphasis. It tells us that the King of Heaven is observing not merely what we claim to believe, but how we walk out what we say we know. This is orthopraxy in its purest form.

Each of these seven assemblies received commendation or correction based on what they did. The Ephesians were praised for their perseverance and doctrinal discernment. Smyrna was honored for enduring tribulation in faith. Pergamos was corrected for allowing compromise. And Laodicea was rebuked for being lukewarm, not in belief, but in practice. This illustrates that transfiguration requires transformation not only of thought, but of habit.

The process of becoming like Messiah, conformed to His image (Romans 8:29), means our behavior must mirror His. The Torah calls us to walk in derekh haYHWH, the Way of YHWH, which is a life of righteousness, justice, mercy, discipline, and sacred action. The assemblies weren’t judged by their theology alone, they were weighed by how their faith manifested in real life.

This is why orthopraxy is revolutionary. Because real transformation isn’t cosmetic, it’s behavioral. It doesn’t happen in abstraction, it happens in daily choices. Messiah didn’t say, “You’ll know them by their doctrine.” He said, “You shall know them by their fruits” (Matthew 7:16).

So if He says, “I know your works,” the question we must ask is: what do my works say about me? Am I being transfigured by the renewing of my mind and the reforming of my walk? Because ultimately, it’s our orthopraxy that proves the authenticity of our transfiguration.

Building on this principle, we find from the article “On the Orthoprax and Anti-Theological Nature of the Hebrew Bible,” the author says:

“The true revolution of the Torah is not in its theology, but in its demand for conduct, its insistence that human beings behave in particular ways toward one another and toward the Divine.”

That hits home. Because in the Hebrew Bible, it’s not the belief system that defines Israel, it’s obedience. The Torah doesn’t open with a creed; it opens with a call to walk before Me and be blameless (Genesis 17:1). The revolution of Torah is behavioral.

And the same article drives it deeper:

“The Torah’s concern is not what is believed in the heart, but what is done with the hands.”

Coupling this concern with what Mesora.org’s article on Orthopraxy states about the Way Israel has been commanded to walk,

“Judaism demands action…Torah life is a system of laws that perfect man by guiding his actions.”

In other words, the beauty, the opulence, of orthopraxy is that it’s practical. It sanctifies every part of life. It brings holiness into your hands, your relationships, your money, your time. It demands that you live what you claim to know. That’s wealth. That’s spiritual richness. That’s opulence.

In Transfiguration Movement #31: Follow the Idea, we broke down how every movement begins with an idea. The Hebrew word demut (image, likeness) taught us that we are living reflections of divine intention. Ideas shape identity. But ideas without action are empty. Faith without works is dead (James 2:17).

That’s where we expound on the principle of orthopraxy. But first, let’s consider the dynamic of orthodoxy, which in contrast, can keep folks locked in debates about doctrine while they’re still dysfunctional. Orthopraxy says, “Okay, you know the truth, now walk it out.” It’s truth-in-motion. Orthodoxy is about right belief. Orthopraxy is about right practice. And while the two are intertwined, Torah centers orthopraxy as the test of true faith. As the Talmud teaches: “Great is study, for it leads to action” (Kiddushin 40b). But it doesn’t stop there. Action is the purpose of study.

Orthopraxy (from the Greek orthos, meaning “right” or “correct,” and praxis, meaning “practice” or “action”) refers to the emphasis on correct conduct, both ethical and ritual, as the foundation of religious life. In contrast to orthodoxy, which emphasizes correct belief or doctrine, orthopraxy prioritizes obedience, behavior, and the proper execution of commandments and communal practices. Within Hebraic thought, this aligns with the Torah’s focus on halakha (the way one walks), which governs every aspect of life—moral, civil, and spiritual.

Orthopraxy means living the truth you say you believe. It is the embodied discipline of walking in alignment with divine law—doing righteousness, not just talking about it. In the Kingdom context, orthopraxy is your daily rhythm of repentance, obedience, compassion, justice, and holiness, all expressed through action. It is where faith becomes a lifestyle, where the Torah becomes your compass, and where your transformation becomes visible through your works. It’s not about having the right answer; it’s about walking the right path.

From the article On the Orthopraxy and Anti-Theological Nature of the Hebrew Bible, we read: “The Hebrew Bible’s great revolution was not the deconstruction of pagan polytheism, that had already happened. Its revolution was a complete shift in priority from abstract belief to behavioral action.”

Likewise, Mesora.org states: “Orthopraxy asserts that correct action is the essential and defining element of Jewish life.” The sages didn’t just emphasize what you believed, but what you did with that belief. That’s the whole point of mitzvot (commandments).

As it is written: “You shall therefore keep My statutes and My judgments, which if a man do, he shall live in them: I am YHWH” (Leviticus 18:5).

When you live orthopraxy, you…

- Reflect consistency between your confession and your conduct.

- Create order in your household, your business, your inner life.

- Establish integrity, because you live what you say you value.

- Align with the Kingdom, because the Kingdom isn’t theory, it’s law, structure, and righteousness.

- Transform others, not by preaching, but by practicing.

- Accountability: Orthopraxy demands that we embody what we say we believe.

- Discipline: It brings structure to spirituality.

- Transformation: It changes not just what we know, but who we are.

- Justice: It centers righteousness and equity in our relationships.

- Legacy: It builds generational blessing, not just personal satisfaction.

This ain’t about appearances. It’s about alignment. Orthopraxy is opulent because it is complete. It’s the royal walk of a Kingdom citizen who knows that true royalty is revealed through righteous routine.

Orthopraxy is how you become light; it’s how you embody Messiah, not just to speak or believe in His name.

So how do we begin to cultivate this beautiful walk?

- Start with Teshuvah (Return): Repent. Come back to your Source. Return to the derek.

- Study Torah Daily: Not for religion. For instruction. Learn how to live Kingdom.

- Practice What You Learn: Don’t wait for perfection. Apply one principle at a time.

- Structure Your Life Around Mitzvot: Set Shabbat apart. Guard your speech. Give righteously. Walk in love.

- Be Accountable: Walk with others who are serious about obedience.

- Be Consistent: It’s not about being loud. It’s about being faithful.

Family, let me say this from the depths of my transformed heart: orthopraxy is the path of kings. It’s how we return to Eden, how we reflect the image of Elohim, how we build the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. You can memorize all the theology in the world, but if you don’t walk the way, you’ll miss the train to Zion.

This movement of transfiguration isn’t about impressing people; it’s about becoming whole, and the only way to truly become, is to do.

So let’s walk it out, b’nai Elohim. Let our hands preach louder than our mouths. Let our love look like lawfulness. Let our life drip with the opulence of orthopraxy.

This is our invitation to transfigure, not through mystical hype, but through halakhic discipline.

The time for passive spirituality is over. The Kingdom is not coming with empty slogans; it’s coming through vessels willing to walk in and with the Word. Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and esteem your Father in Heaven (Matthew 5:16).

Our righteousness is our revolution.

Let us not be hearers only, deceiving ourselves, but doers of the Word (James 1:22); let the opulence of orthopraxy be our new norm.

Let our walk of orthopraxis be our catalyst for our transfiguration.

Amen.

Selah.

Discover more from SHFTNG PRDGMZ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Aharon N. Varady (transcription)

the Open Siddur Project ✍ פְּרוֺיֶקְט הַסִּדּוּר הַפָּתוּחַ

Aharon N. Varady (transcription)·opensiddur.org·

Concluding Prayer for Hallel in the Home Service for the Festival of Passover, by Rabbi J. Leonard Levy (1896)

This is a concluding prayer in the Hallel service at the Passover seder by Rabbi J. Leonard Levy to his Haggadah or Home Service for the Festival of Passover (1896) pp. 32-34. The prayer does not appear in subsequent editions. The prayer threads the needle between the particularly Jewish communal focus of Passover and the…

What separates תפילה from תחנון? A blessing requires שם ומלכות. Shemone Esrei does not contain שם ומלכות. Yet it functions as the definition of a blessing. As does kadesh, which also lacks שם ומלכות. For that matter so does ברכת כהנים וגם כן קריא שמע. The k’vanna of חנון has nothing to do with the formal prayer written in the Siddur. Why? Because all these “mitzvot” qualify as tohor time oriented commandments which require k’vanna. What’s the k’vanna of תחנון through which it defines תפילה?

Word translations amount to tits on a boar hog when the new born piglets are ravenous and the sow died after giving birth! The 5th middah of the revelation of the Oral Torah at Horev – חנון, serves as the functioning root שרש of the term תחנון תפילה. The tohor time-oriented commandment of תפילה learns from the additional metaphor of תחנון. Consider the Order of the Shemone Esrei blessings … 3 + 13 + 3 blessings. 6 Yom Tov and 13 tohor middot revealed to Moshe, 40 days after the ערב רב Israelites – Jews assimilated and intermarried with Egyptians, no different from the kapo Jewish women who slept with Nazis. This ערב רב, according to the Torah – as expressed in the memory to war against Amalek/antisemitism – they lacked fear of אלהים. This same ערב רב referred to their Golden Calf substitute theology by the name אלהים. This tie-in explains the k’vanna of the term “fear of heaven”.

The ערב רב Jews lacked “fear of Heaven”, and therefore their avoda zarah profaned the 2nd Sinai commandment. Hence when Jews assimilate and intermarry with Goyim who do not accept the revelation of the Torah at Sinai (neither the Xtian Bible nor Muslim Koran ever once brings the שם השם first revealed in the 1st Sinai commandment – the greatest commandment of the entire Torah revelation at Sinai and Horev! Do Jews serve to obey the Torah revelation לשמה או לא לשמה? Observance of all the Torah commandments and Talmudic halachot hangs on this simple question.

Therefore תפילת תחנון interprets the k’vanna of תפילה, through the concept that a person stands before a Sefer Torah and dedicated specific and defined tohor middot which breath life into the hearts of the Yatrir HaTov of the chosen Cohen oath brit people. The verb תפילה most essentially entails the k’vanna of swearing a Torah oath. What Torah oath? The dedication, think korban, of some specified tohor middot…. Hence the concept of תפילת תחנון.

LikeLike