________________________________________________________________________

…Since Shemayah was the Nasi – the Torah leader of the [Israelite] people – he knew the importance of humility. For a leader’s prominence comes as a result of his selflessness. Because he has no concern for himself, he is fit to serve as a medium to lead his people to an awareness of [Elohim]’s sovereignty…

Sichot Kodesh, Shemini, 5728

A capable servant will dominate an incompetent son

And share the inheritance with the brothers.

Proverbs 17.2

________________________________________________________________________

It’s a well established dynamic of history that before chattel enslavement, servitude wasn’t synonymous with chains, brutality, dehumanization and inhumanity. In fact, in ancient cultures, specifically those of African, Hebrew, and Near Eastern societies, servants played vital, respected roles. In that context, servitude was often a temporary condition for restitution, survival, or apprenticeship. In the Torah, servanthood usually served as a path to restoration, not reduction. In that particular society, servitude wasn’t about erasure of humanity but the cultivation of character. As circumstance would have it, some even voluntarily entered into servitude for stability, honor, or proximity to greatness. For those peoples of ages bygone, there was dignity in being trusted with someone else’s household, with stewarding resources and caring for people. It required discipline, wisdom, patience and most especially self-mastery.

But then came the Transatlantic Slave Trade, or what is also known as the Maafa – the great disaster.

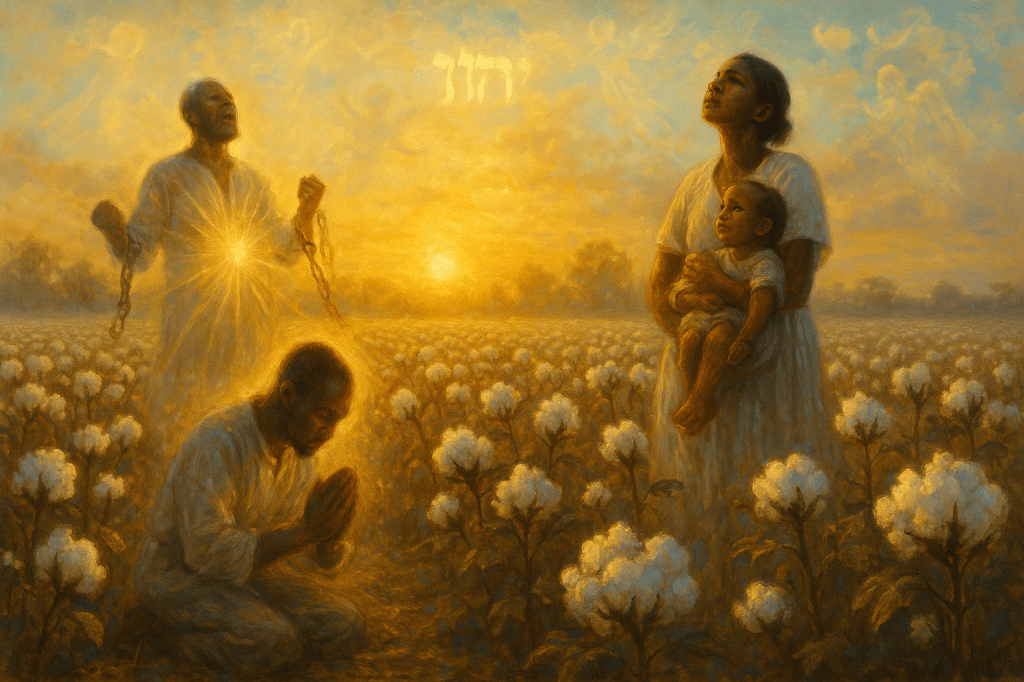

From there our story as a people takes a brutal turn. The so-called African-American experience with servitude became synonymous with forced labor, cultural annihilation, systemic dehumanization, and generations of psychological and epigenetic trauma. But even in that context, our ancestors modeled something supernatural; they sang in chains, they created in cotton fields, they prayed, preached, and praised while being hunted, harassed and hated. And if you look closely enough, you’ll see that while our ancestors may have been in bondage, they never stopped serving something greater; YaH, family, hope, future…and to do that takes mastery.

Unquestionably!

It takes a different kind of strength to serve with dignity in an undignified position, and when taking into account the purpose of the servitude, the process of the experience facilitates the essence of what transfiguration is all about. Relative to this position, we find that the dignity to which is referred is not merely a matter of escape from pain but more so that of elevation in purpose; the power to become something greater while still in circumstances that would break a lesser soul.

But let me be unequivocally clear: involuntary servitude is not righteousness, nor is it the ideal. In fact, the Torah doesn’t honor bondage in the least, rather Torah sanctifies choice. There is a world of difference between being forced to serve and choosing to serve, as one is oppressive and the other, aligning. One is slavery, the other is discipleship. Once this is reconciled, the rest is granted.

But to take this a step further, here’s an unpopular prophetic principle to grapple with; one we can’t ignore if we’re really about this Kingdom work and walk. The truth of the matter is that many of us, iself included, have learned servitude the hard way. In all humility, I sure enough know for one that I didn’t learn how to serve because I was an eager student of the Most High; because being that I was a hardheaded child of the Covenant who set on serving self, I had to go through some things. But the Torah is clear: if we refuse to serve our Elohim with joy and gladness of heart when we the opportunity, then we’d be taught how to serve our enemies in want, in hunger, in thirst, in nakedness, and in lack of all things. That’s Deuteronomy 28:47–48 all day, every day! We were warned, and straight up told but we had to find out the hard way.

And our experience? It’s not just mythological or historic, it’s prophetic evidence of our reality; a living witness. For many of us, the awakening to our identity as Yisra’el didn’t come through tradition, but through trauma. Through tracing pain back to prophecy. We didn’t find ourselves in the Book of Life, we found ourselves in the curses. Specifically, Deuteronomy 28. We didn’t get in through the front door of honor and esteem, we came through the back door of suffering. And make no mistake, the signs were written all over us; not just physically, but spiritually, politically, culturally, economically, and socially.

But let’s be even more precise: our identifying marks as the remnant of Israel in the latter days are not rooted merely in oppression, but in disobedience, another unpopular prophetic principle. Our condition is not just the result of hatred from other nations, it is the result of our having broken covenant with the Most High, and this is the part we gotta reckon with. Torah never said we’d be identified by our swag, our skin tone, or our style, but by the consequences of not listening.

All these curses shall befall you; they shall pursue you and overtake you, until you are wiped out, because you did not heed your God יהוה and keep the commandments and laws that were enjoined upon you. They shall serve as signs and proofs against you and your offspring for all time…

Deuteronomy 28:45–46

This right here is the turnkey, not just that we were forced to serve in lands that are not ours, but that we failed to serve our Father and King in our own land with joy and gladness of heart. What we have to acknowledge, accept and embrace is that the curse didn’t begin with foreign chains, they began with a forgotten covenant. We were not just disobedient; we were ungrateful. For us, the commandments aren’t simply rules, they’re the essence of relationship. And when that relationship was abandoned, the consequences weren’t just individual, they were generational and national.

I propose to you, beloved reader, that the signs that identify us as Israel in these end times are not merely in the blessings or the captivity, rather they’re found in the prophetic fingerprints of Deuteronomy 28. These curses are not just punishment, they’re the smoking gun evidence of just who we are. And they’re also proof of what we lost and to what we must return. That’s why verse 46 says, “They shall serve as signs and proofs against you and your offspring for all time.” The curses were designed to follow us, to mark us, and ultimately, to remind us, not of how far we’ve fallen, but of how far we must return.

And let’s be clear: our ancestors didn’t just get conquered, they got corrected. Hard as it may be to accept, our fathers and mothers had to learn the value of servitude the hard way, by being made to serve nations who neither knew nor honored our Elohim. What was meant to be joyful service in the Kingdom became bitter bondage in the empires of men. And yet, even in that, YHWH’s mercy left a remnant; It left signs, testimonies, and awakenings and most importantly, It left a path back. Because the redemption isn’t just in being freed from our enemies, it’s in becoming faithful servants again. This is what our Messiah taught when He said the greatest among you shall be servant of all. That’s not just humility, it’s healing; people, that’s not just social order, that’s Kingdom order!

So let’s not just identify the curses, let’s break their cycle and return to the blessings. This is why we at Beit Mashiyach read the first fourteen verses of Deuteronomy 28 before our prayer and studies; to refamiliarize ourselves with our purpose and the good that follows when we are living according to our purpose. And the key to our unlocking our purpose is this: our return to the covenant; our return to serving YaH with joy, our return to serving one another with reverence. Because when we return with the full understanding that servitude to YHWH is the key to our freedom, while rebellion is bondage, we open the door to the blessings once again. When we serve the Most High in Spirit and in Truth, with the gladness our ancestors abandoned, we reverse the curse, restore the relationship, and reenter the promise.

And then when that happens, the signs won’t just be proof of punishment, they’ll become our testimonies of transformation, the markers of our Abba’s mercy, the evidence that we, as Israel, once lost, are found; that we were oce scattered, now we have been regathered; that we were once cursed, but now we’ve been recommissioned and repositioned to serve, not as slaves of Pharaoh or Rome or Babylon, but as priests of the Most High. For we are a Kingdom of servants, created to be clothed in joy and light.

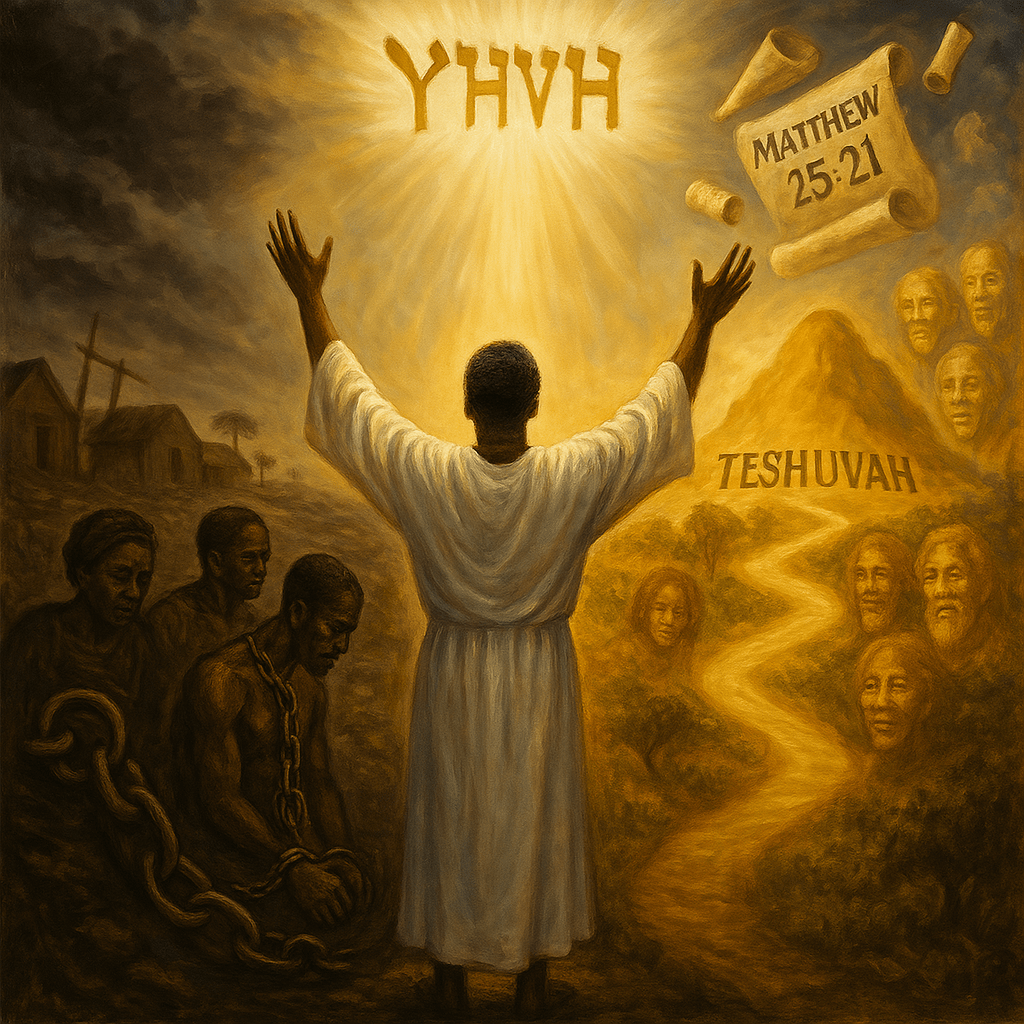

So what’s the remedy? Something that we’ve discussed in nearly every writing of the Transfiguration Movement; teshuvah, our return; our repentance, our faithful return to the covenant. Our faithful return to serving YHWH in Spirit and in Truth. That’s how the curse gets reversed and our condition ameliorated, that’s how our trauma becomes testimony, that’s where we stop being victims of history and start becoming prophetic vessels of redemption. That’s how we’ll hear these most reassuring words from our Master found at Matthew 25.21,

Well done, good and trustworthy servant. You were trustworthy over a little, I shall set you over much. Enter into the joy of your master.’

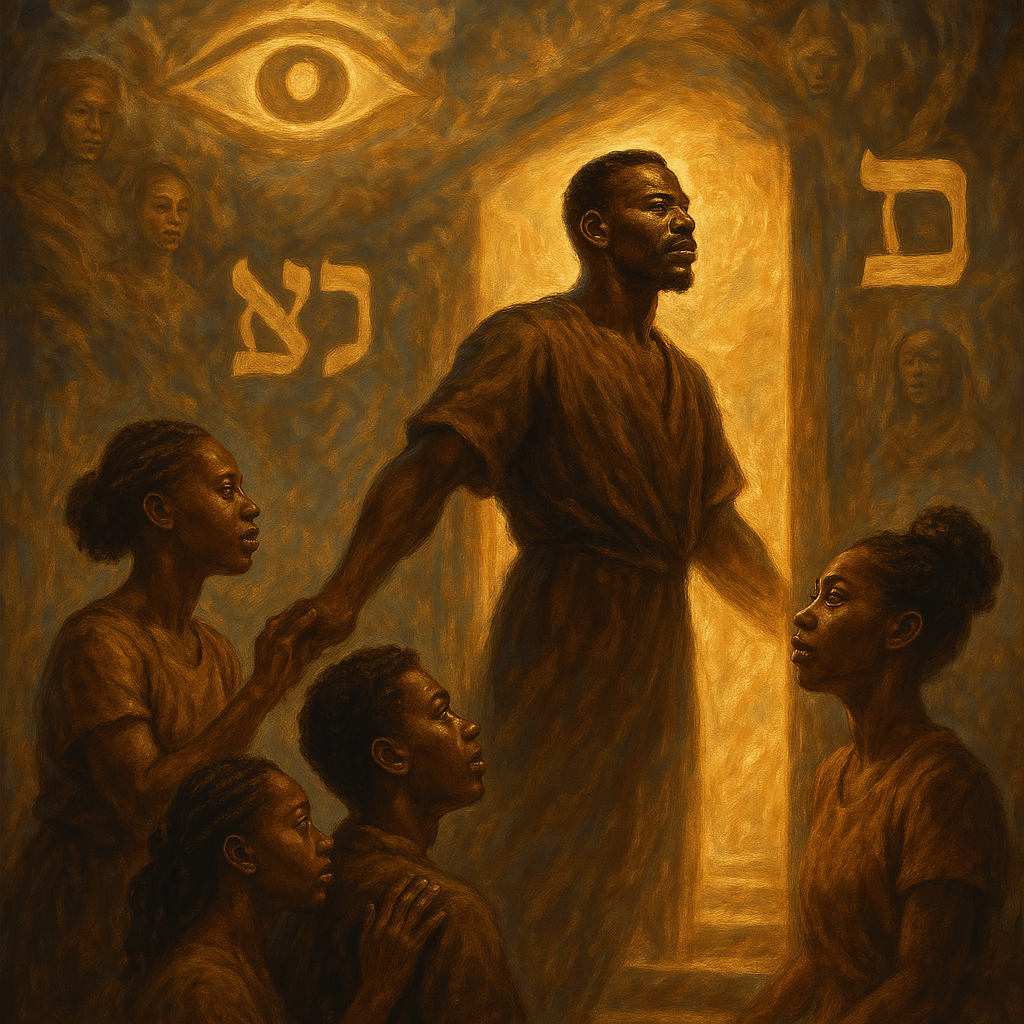

The Hebrew word for “serve” is avad (עֲבַד) and the word for “servant” is eved (עֶבֶד). Same root, same dynamic, same letters, different pronunciation. But looking into these letters, we find the following:

- Ayin (ע) – the eye, representing insight, perception, vision.

- Bet (ב) – the house, family, dwelling, the heart of covenantal belonging.

- Dalet (ד) – the door, pathway, decision point between what is and what can be.

Put them together? Avad isn’t just about labor, it’s about seeing the house through the door. It’s about choosing to enter and serve from vision. It’s spiritual work. Conscious alignment. Not just physical motion, but heart devotion. When you avad, you don’t just work, you worship, you serve with joy and gladness. You don’t just act, you align.

But if the servant declares, ‘I love my master, and my wife and children: I do not wish to go free,’ his master shall take him before Eloah. He shall be brought to the door or the doorpost, and his master shall pierce his ear with an awl; and he shall then remain his master’s servant for life.

Exodus 21.5-6

This passage from Shemot speaks to more than a legal rite regarding ancient Hebrew servitude, it reveals the hidden path of transfiguration and the sacred science of self-mastery. The servant who declares, “I love my master, my wife, and my children; I do not wish to go free,” is not merely forfeiting his independence, he is choosing, rather, to abide in the house of covenant by love, not by compulsion. This is the transition from obligation to willing submission. It’s the moment when the soul recognizes that freedom without purpose is a form of bondage, and that true mastery is found in surrendering to the order and intimacy of holy relationship.

In this event, the master takes him to Eloah, then to the doorpost, a threshold, a seemingly insignificant space between outside and inside, between exile and inheritance, and there he pierces his ear with an awl. This ear, once tuned to the noise of wanderings, is now sanctified to hear only the voice of the Master. The doorpost, previously smeared with the blood of the lamb during Pesach, is now the place where blood seals a personal covenant. This act is not the end of servitude but the beginning of sonship, an entrance into the household of faith. This is transfiguration, not of the outer form, but of the inner identity. The one who once served by command now serves by communion.

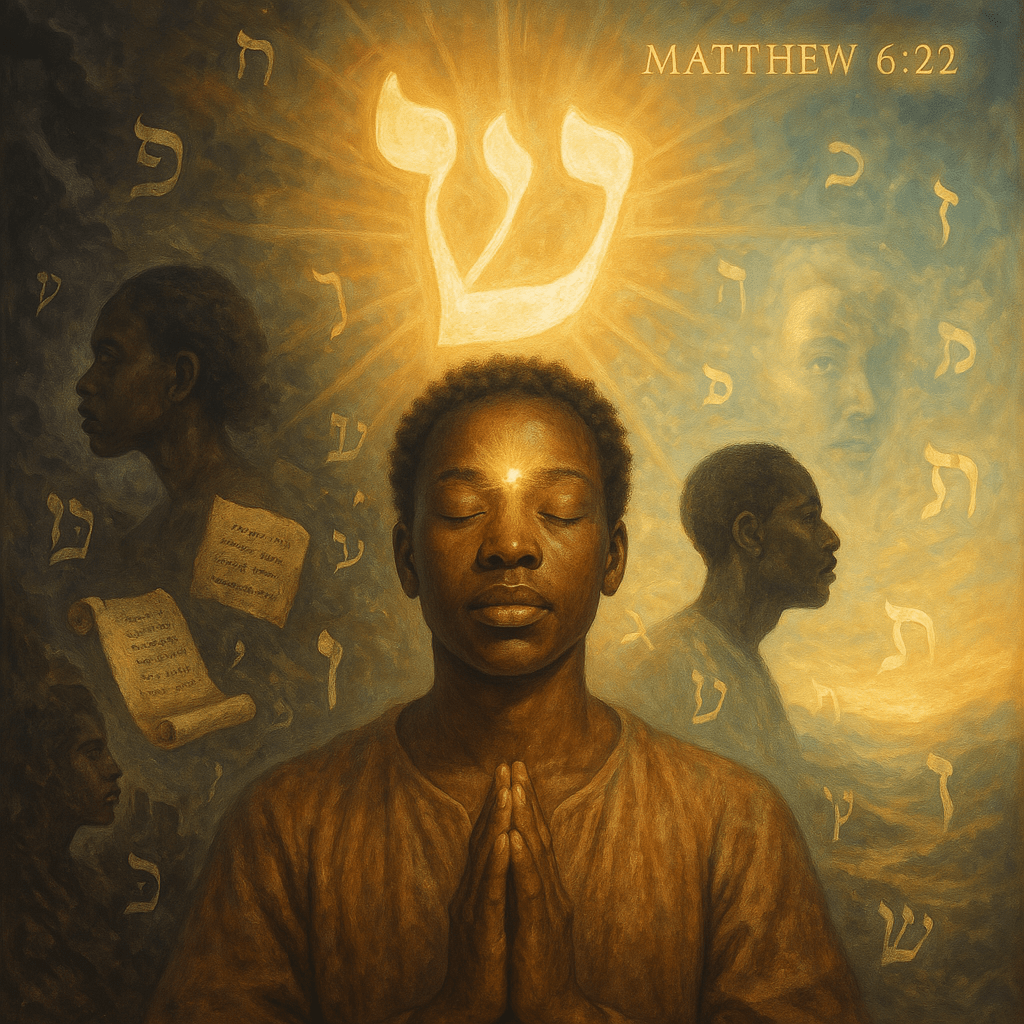

As we’ve seen, the Hebrew word for servant has encoded in its letters the very architecture of this mystery. The first letter, Ayin (ע), means eye, a symbol of perception, inner sight, and awakened consciousness. In the realm of true servitude, this is not about blindness or subjugation, but about seeing clearly with the inner eye, the ayin panim, the face within the face. The servant’s journey begins with vision, because perception determines posture; if the eye is clouded by pride, fear, or distraction, service becomes performative and hollow. But when the eye is made single, focused, and undivided, one begins to perceive the will of the Master not as tyranny, but as instruction, correction, and alignment. This inner seeing is the gateway to transfiguration, the moment when the lower nature is illuminated by the higher light, and the one who once served out of obligation now serves from joy, devotion, and trust. Self-mastery depends on this inner sight, because one cannot govern what one does not recognize. Ayin, therefore, opens the path to wisdom, for it is the ability to discern not only what is seen, but what is unseen; to navigate the house and the door with intention. As Mashiyach tells us in Matthew 6:22,

The lamp of the body is the eye. If therefore your eye is good, all your body shall be enlightened.

From this it becomes clear that our eye must be able to discern the light of purpose.

The second letter, Bet (ב), represents house, not just a physical dwelling, but the inner sanctuary and sacred space within where identity is shaped, where the soul is sheltered, and where order cultivates purpose. Bet is the first letter of the Hebrew word for Genesis, B’reisheet, “in the beginning,” a holy call reminding us that all creation unfolds from and within the principle of the house. It is the place where covenant begins, where boundaries are not limitations but dwellings of love and law. It is the domain where the servant becomes more than a laborer; he becomes a trusted member of the household, a steward of the mysteries of his Master. Service without being a member of h’bayit, the house, which gives the feeling of belonging, a sense of roots, and the vibration of rhythm, is disconnected, hollow and mechanical. But the servant who chooses to stay has discerned the difference between working in the house and dwelling in it. They have found rest, not in personal ambition, but in the structure and flow of their Master’s will. The house is no longer a workplace, it’s now a womb for rebirth, a sanctuary for shelter, a temple for worship. Their decision to remain is an echo of the soul’s choice to abide in alignment with holy purpose; to become one with the order of the household of faith.

The final letter, Dalet (ד), signifies the door, the threshold between dimensions, the place of passage between what was and what shall be. It is not merely an exit or entrance, but a moment of decision that determines direction. In the servant’s ritual, the dalet becomes sacred space, where covenant is sealed not with chains but with choice. He does not flee through the door into a counterfeit freedom rooted in ego or rebellion; rather, he offers his ear, the symbol of listening and obedience, to be pierced beside it. This act binds him not in bondage, but in allegiance to a higher will. The ear, aligned with the shema, becomes a vessel through which the voice of the Master enters and reverberates. True transfiguration begins at this door, where one transcends mere servitude and is transformed into a vessel of divine purpose, entering a house not built with hands but with wisdom, discipline, and love. The dalet, then, is the hinge on which destiny turns, and to be affixed to it is to live in constant readiness to hear, obey, and become.

The mystery deepens when we recognize that Yeshua the Messiah, the suffering Servant, became the ultimate eved, pierced, obedient, and faithful to the Father’s house. His transfiguration was not limited to Mount Tabor; it was the fruit of His lifelong submission. As it is written,

He learned obedience by the things He suffered

Hebrews 5:8

It is through that obedience, that Yeshua became the doorway for many. Likewise, the soul that surrenders to become a servant by choice steps into the same spiritual lineage. Through sight (ayin), dwelling (bet), and voluntary sacrifice at the door (dalet), we are no longer bondservants of the flesh but sons and daughters who manifest the light of our Master, forever marked by love. It is written,

For he who is called in the Master while a servant is the Master’s freed man. Likewise he who is called while free is a servant of Messiah. You were bought with a price, do not become servants of men.

1 Corinthians 7.22-23

This passage begs the questions, what if servitude isn’t a curse, but a classroom? What if the hardship of our ancestors was meant to break the flesh so that our spirits could rise through transfiguration? And what if we’re the generation to flip the script, the ones called to serve with vision, to build the house, and to open the door for others?

I say that we are, and that what we’re called to do, right here, right now… that’s real eved, and we’re the the real avad, and that which we are accomplish, takes real self-mastery.

And that’s the Transfiguration Movement, my people.

So let’s take a moment to consider more deeply just what is an eved? A servant is someone who perceives (ayin) how to bring order and presence (bet) into a new realm of movement and transition (dalet). In other words, the servant is the visionary vessel who creates doors for others to walk through. True servants aren’t weak, they’re seers, shakers, shapers, and stewards of transformation. Servants are leaders who create more leaders for the sake of transformation and upliftment. Servants are those who love their El and their people more than they love themselves and are willing to lay their lives down for their El and their people because they realize that the whole is greater than the part, but that it takes every part to contribute selflessly to the whole.

That’s why Messiah Yeshua said,

Whoever desires to become great among you, let him be your servant

Matthew 20:26

He wasn’t just humbling folks for humility’s sake, instead He was giving us a cosmic key. Leadership that doesn’t first pass through servanthood is hollow, because real leaders serve into power, not snatch it.

Consider the greatest of those among us, from Frederick Douglass to Harriet Tubman, John Brown to Marcus Garvey, William Crowdy Saunders to Ben Ammi Carter, Dr. King to Malcolm, from Ella Baker to Fannie Lou Hamer; every single last one of them modeled this quality. They weren’t driven by ego but by duty. They led through service, and they mastered themselves so they could empower others who motivated them to serve with love. That’s the definition of a servant-leader.

Dr. Howard Thurman once wrote, “Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.” Servants come alive when others are lifted. That’s the paradox: in serving, we discover ourselves.

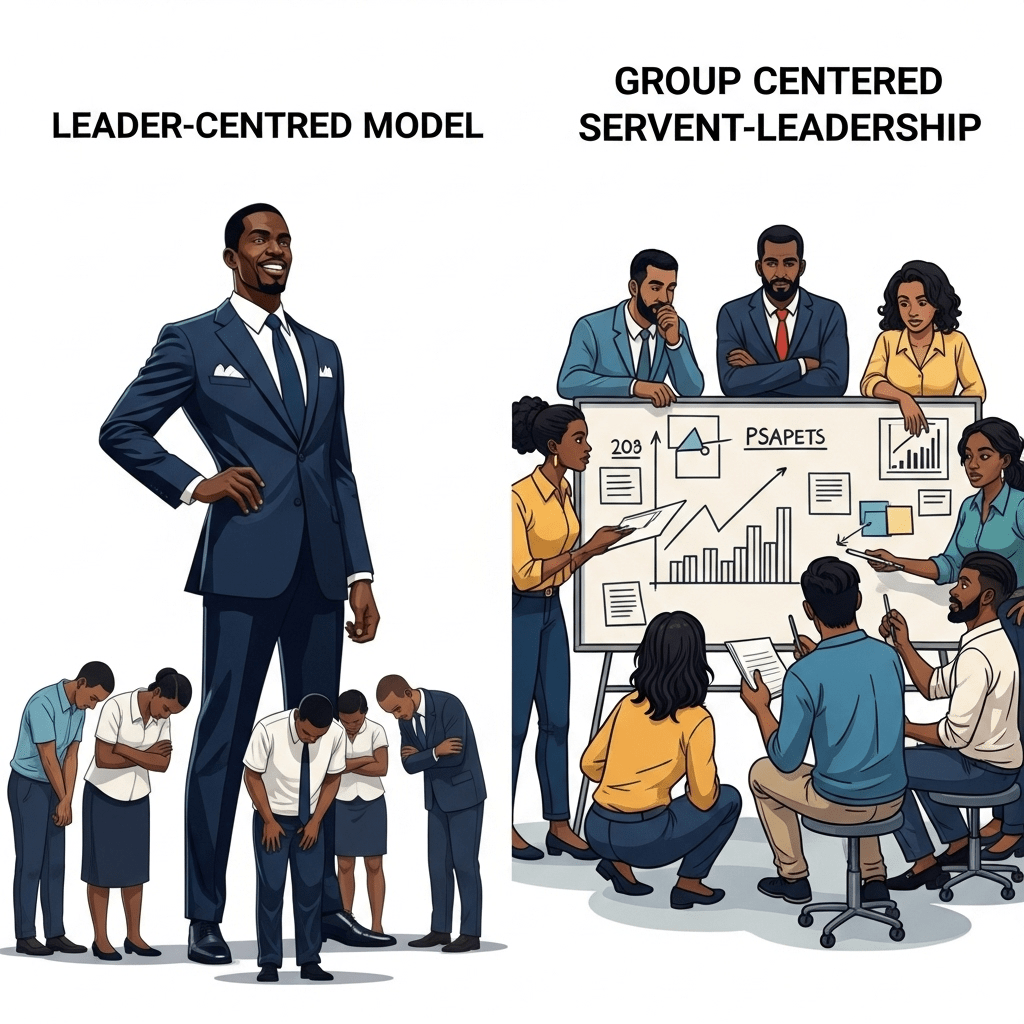

In this light, it becomes apparent to see the contrasts and pitfalls of leader-centered models, where charisma often replaces character and ego eclipses collective purpose. But on the other hand, it’s group-centered servant-leadership that restores balance by emphasizing the strength, wisdom, and responsibility of the whole. Rather than one figure at the top directing passive followers, this model recognizes that leadership is a shared charge, and each member contributes uniquely to the mission.

In the servant-leadership framework, authority is not domination but facilitation; the leader serves by cultivating others, discerning the group’s needs, and helping each part function in alignment with the whole. When the vision is carried communally, the burden is lighter, the insights are deeper, and the results more sustainable. This pattern, reflected in the priesthood of Yisrael, includes all believers and the structure of the early assemblies, reminds us that no single person embodies the fullness of the purpose, but together, in humility and mutual accountability, the body can move toward transfiguration. It also informs that we are the Messianic figure that we’ve been waiting to manifest. The failure of many modern movements and institutions lies in elevating the leader above the people; but in the Kingdom, the greatest among us is servant to all.

So in full consideration of this path to self-mastery, it begins not with self-exaltation, but with surrender; first to a higher purpose, then to disciplined service. Servitude in this context is not oppression, but refinement; it is through consistent, humble acts of obedience, accountability, and sacrificial love that the self is shaped, purified, and aligned with divine order. By yielding our will to righteous structure, we train the impulses, harness the emotions, and awaken the deeper capacities of soul. This process is the stuff that faith is made of. And when we truly move in faith, we find that in serving others with intention, we come to know our own purpose more clearly. The doorway to mastery is found not in dominance, but in devotion. Here are a few steps that I have found have helped me draw closer to self-mastery as I humble myself and learn to serve.

Steps Toward Mastery Through Servitude:

- Submit to a Higher Vision – Align with the Most High’s purpose, not popularity.

- Practice Humility – Let correction shape you. Don’t run from low places.

- Serve in Silence – Everything doesn’t need applause. Yah sees in secret.

- Be Faithful Over Little – Your consistency in small things opens big doors.

- Multiply Others – Make space for others to lead. That’s legacy.

- Guard Your Heart – Servitude can get heavy. Keep your joy intact.

- Elevate Your Vibration – Serve from wholeness, not from brokenness.

With these steps taken, we will be able fully experience that to become self-mastered is to be forged by holy intention and not by fleeting ambition. It begs to be keenly aware, as we’ve stated time and time again, that this journey begins with our submission, not to man, but to a higher vision that calls us to align with the Most High’s will and purpose rather than chase after applause or popularity. This kind of alignment sharpens discernment and anchors the soul beyond the sway of trends. In this process, humility becomes the cornerstone of growth; it invites correction, even from discomfort, knowing that low places are often where our roots deepen and our character is carved. In this way, silence becomes sacred ground for us, where we serve not for validation but for transformation, trusting that YaH sees in secret and rewards openly. Our faithfulness in the small, often unnoticed things, becomes the training ground for greater stewardship. This is because it’s not the size of the task but the spirit of the service that expands the soul. True mastery refuses to hoard influence, instead it multiplies others, creating room for their emergence and succession.

This is legacy, not a monument to self, but a seedbed for generations. Yet and still, though, the weight of servitude can be heavy, as guarding the heart becomes essential to preserve joy, compassion, and vision. Finally, we elevate our vibration through inner healing, allowing our service to flow from wholeness rather than brokenness. A fractured vessel leaks, but a healed one overflows. Thus, in serving with integrity, we are slowly mastered, not by force, but by love.

So here’s my challenge to us:

Don’t run from servitude. Rethink it. Reclaim it. Redeem it.

Be the kind of leader who can wash feet and still part seas.

Be the kind of servant whose light confuses the proud and inspires the lowly.

Because the world doesn’t need more rulers. It needs more righteous stewards.

Let every teacher, artist, healer, parent, preacher, and visionary rise in the spirit of servant-leadership. Let us not just speak truth but serve truth. Let us be a people who embody the mastery of servitude, shaping the world not from above it, but through it.

“He took the form of a servant…and was exalted” (Philippians 2:7-9).

He took this step because he knew that servitude is not a step down. It’s the first step up.

So let’s keep on stepping in humility, willing to serve our Father and one another with joy and gladness. Because it is through this dynamic that we are empowered, and when we move in this power, the transfiguration because our reality, and reality is what we are called to bring forth.

So Lazarus, come forth; Tabitha, rise!

Your transfiguration awaits you.

Selah…

Discover more from SHFTNG PRDGMZ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 Comments